This discusses how I go from having a fungus to examining it under the compound microscope. This mostly applies to ascomycetes, and I’ll use a few examples.

1. Octospora / Lamprospora / “discomycetes”

Generally, the bryoparasitic Pyronemataceae are fairly large, so mounting entire apothecia often results in preparations that are too thick to be very useful under the light microscope. For these, I often scoop out a tiny portion of the hymenium (middle part) of the disc. This means that I still have material left over if I want to re-examine the specimen in the future.

Place the tiny fragment onto a (small) drop of water on a microscope slide. Make sure it’s as small as possible. You can use a pair of dissecting needles to crudely cut it up more once it is on the slide. Make sure the fragments are small enough so that when you put a cover slip over the preparation, it gets squashed without the requirement for much additional force (this can deform spores). You can give the coverslip a tap or light press with the back of a finger nail to spread the contents of the slide.

Another method for examining these fungi, though I do not often find the need to use it, is to make sections of the apothecia. There are many ways to do this and each person has their own preference.

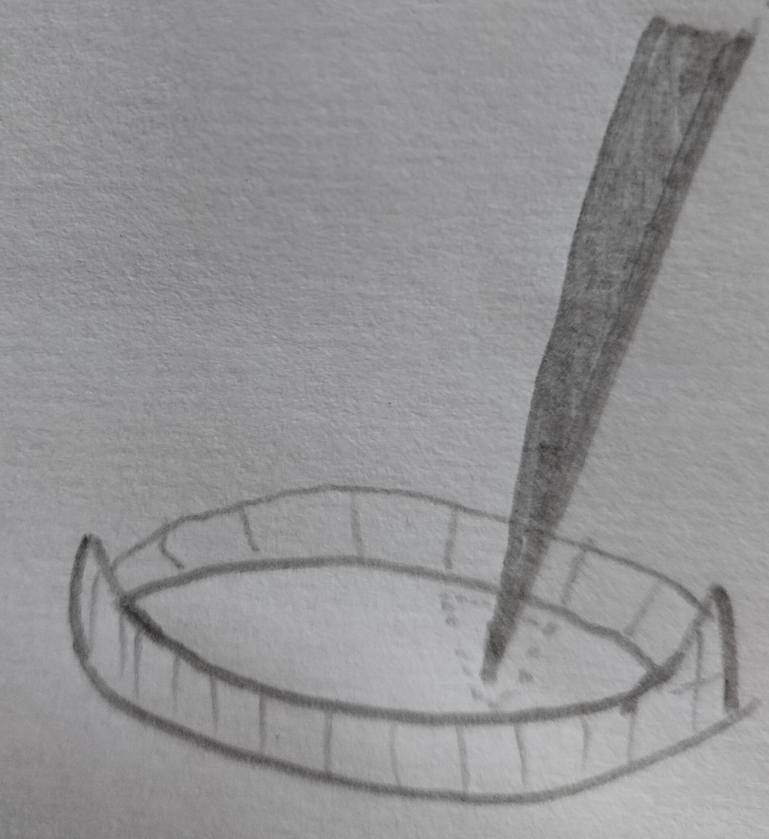

I take a hydrated apothecium and remove excess water by blotting it on a pit of kitchen towel before placing it on a slide, letting it dry out for some time (10 mins at least). If too damp, the tissues will be like jelly and fold / break during the sectioning. Under a dissecting microscope, I use a razor blade and make careful cuts through the apothecium after cutting away about 1/3 of it so that I make sections from around the middle. The sections should stick to the blade (if the specimen is too dry, they may flick away – prevent this by running the blade through a drop of water so that they stick), so it’s important to remove them gently with a dissecting needle. You can move them to a fresh drop of water, add a cover slip and then examine under a compound microscope.

Infection structures of bryoparasitic Pyronemataceae can be distinctive. Since they are on rhizoids, it is important to take infected shoots with a bit of soil. Tease hydrated moss shoots apart (quite thoroughly but try to keep the rhizoids intact) and wash off excess soil particles in successive drops of water (until you don’t see particles coming off) on a petri dish or slide under a dissecting microscope. You can use a dissecting needle to push away large debris. You can also place shoots into a sieve and pour running tap water over them but you need to pull them apart first or the rooting system will bind the soil together.

Once the shoots are clean, the rhizoids can be removed using fine forceps and moved to a clean slide. I usually put a drop of lactophenol cotton blue directly onto a clean slide and put the rhizoids directly into that as this stains fungal hyphae and appressoria blue.

You can see the results of a lactophenol cotton blue stain of rhizoids in a high magnification micrograph on Jan Eckstein’s website here http://octospora.de/Odoebbeleri.htm

2. Bryocentria brongniartii and other species with tiny ascomata

With these, if they are known species or in the first instances of examination, I usually make a simple squash mount of whole fruitbodies. With B. brongniartii, I carefully transfer a few fruitbodies from an infected host plant to a small drop of water on a clean slide. Once there, one may rupture the fruitbodies by crunching them with a pair of fine forceps to release the contents, or place a coverslip over the drop and tap or press it with the back of a (clean) finger nail. This should result in ruptured fruitbodies with their contents spilled out around them, so asci and ascospores can be seen. The reason I use multiple fruitbodies is because sometimes they are either overmature (spores released) or immature (spores still developing).

You can also try to section these, though it is difficult and some (E.g., Bryochiton) are just too small to do by hand. A good idea is to section the fruitbodies when they are attached to the host. This way, you might be able to see the mycelium and how the fruitbodies emerge from it in the host tissues. Sectioning the leaves (and fungi on them) of Polytrichaceae is a good way to practice.